Where is home? Is it the motherland, the left-behind world of birthplace and ancestry, or is it the strange but fresh landscape of possibility and promise? Which language articulates the private self, which the public? … What is the cost of such unwilling or hopeful migration?” (Moscaliuc and Waters 2006)

Four years ago, I distinctly remember spending a short cab ride with a white male driver who assumed I was born here because of the way I assimilated the Canadian English accent. When I told him I am native Filipino, he carefully asked if I was working as a nanny in Kelowna. It was a disembodying experience—I immediately thought of the painful realities Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) experience around the globe. A shameful shock registered as my second reaction. I recall collecting myself and thanking him for thinking that I am capable of copious amounts of skilful care. ‘I’m but a graduate student who is striving and struggling to finish her dissertation’ I said. Needless to say, he was shocked for a few uncomfortable, yet satisfying, minutes.

I recall this narrative from the draft of my monograph to highlight the symbolic violences of micro-aggressions that permeate white settler culture in North America—particularly those that constantly question one’s identity and, in turn, make the individual question their own identity. These symbolic (and often material) violences disrupt the migrant’s struggle for belonging and a sense of space amidst the challenges of visas, citizenships, and alienation.

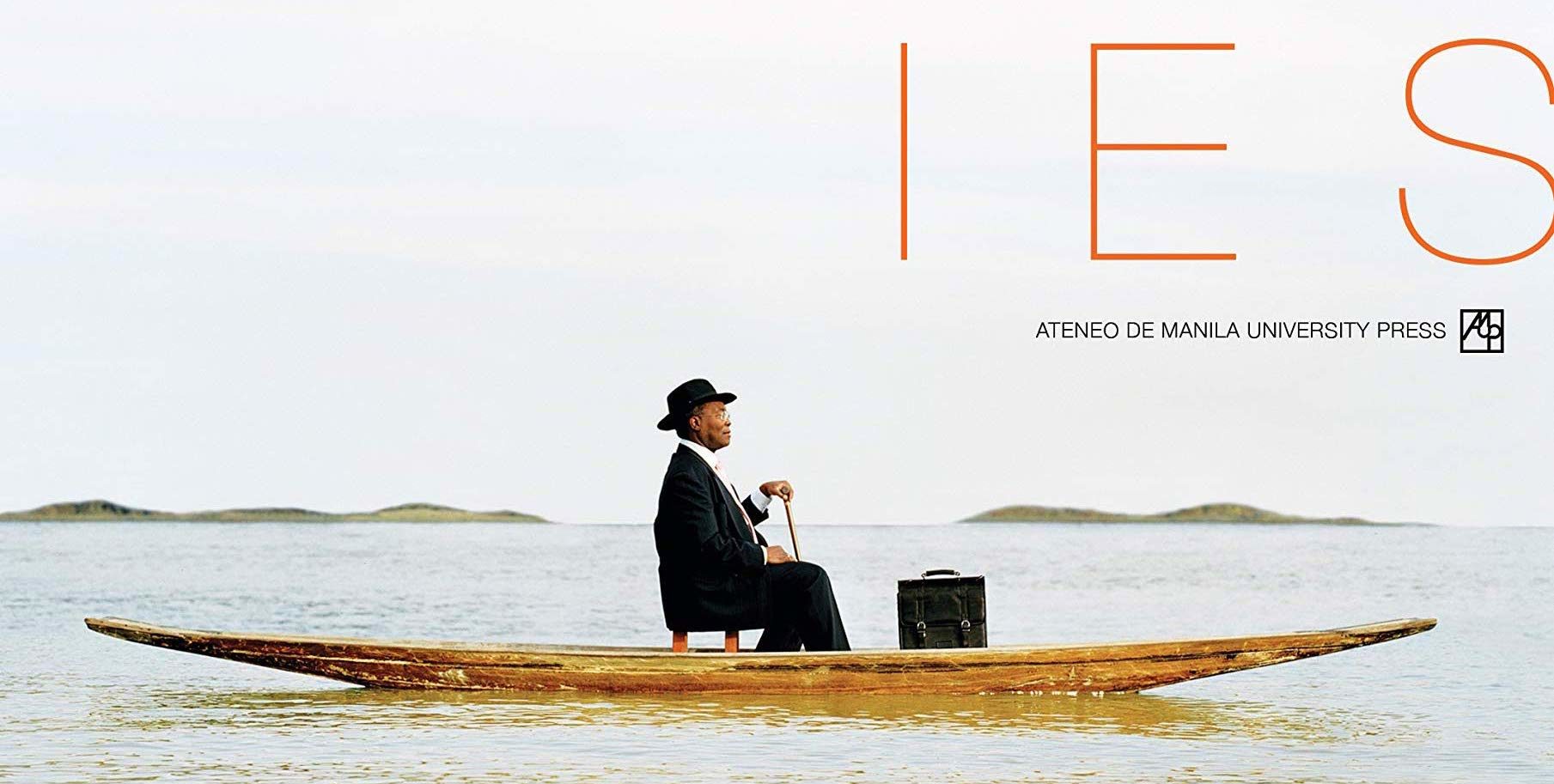

Under the nation-state of the Philippines, the migrant is revered as the Bagong Bayani. The Bagong Bayani’s selfless sacrifice to migrate sustains the country’s economy and pays for the billions of dollars in plundered and corrupted national debt. Further, the Bagong Bayani has become the pinnacle of abundance. They have created a new economy based on their remittances and their balikbayan boxes — big 24x18x24-inch packages with limitless weight sent across oceans. Balikbayan boxes are skillfully stuffed to the brim with non-perishable items found only in developed countries—unattainable back in the homeland without a significant amount of wealth.

For this reading group, I am inviting readers to contemplate the concept of migration and what that yields for the fields we are invested in. In my case this is for ecocriticism. I also want to direct the focus towards the migrant and their existence in the liminal environment. I will ask questions such as:

- How has migration been weaponized as an economic symbol to push many women in developing countries to leave their homeland and families behind to become warm-body exports in a foreign country?

- How does a migrant survive, thrive, and struggle in the liminal environment?

When engaging with these questions, we also want to ask ourselves—what does the migrant lose and, hopefully, regain in the process of undertaking these movements? It is my intention to facilitate a space that sparks conversations about how migration as an analytic can decentre many western-leaning frameworks that focus on place, identity, and nation-building. I will try to direct our focus towards ideas that are constantly unsettled by movements of the current perilous times to think through literary and cultural modes of production.

Reading group event details

Date: 2nd August 2023

Title: Working with the liminal: Thinking of a migratory consciousness

Speaker: Rina Garcia Chua

Chair: Nadeen Dakkak

Minutes: Maria Jose Recalde-Vela

Selected minutes

Rina writes poetry to respond to migrant workers and their plights. She had the opportunity to do so after having access to archives. Since not everyone has access to archives, poetry is one way to bring this knowledge to people.

“I’m from the Philippines and I was born in Manila and that’s important to my scholarship because growing up, I was very lucky to live and work close to an airport. My mom was a flight stewardess for 35 years with Philippine Airlines and that has affected a lot of my thinking, a lot of my scholarship: The privilege and the peril of flight, and that figures into where I’m coming from right now.”

“So, a lot of my scholarship I owe to something quite different and something that is maybe a territory that folks are still exploring, and not only the environmental humanities but also in literary and cultural studies. And that is writing with our own lived experience and with the experiences that are present in our bodies. And I direct my thinking in a way that I constantly have self-reflexivity in my scholarship. And in the experiences that happened to me, especially since I am kind of situated in what I would like to call the liminal or the liminal environment.” – Rina

The ‘liminal’ or the ‘liminal environment’ is a common thread in Rina’s thinking, and it reflects in her poetry and scholarship. Rina encourages writing with our lived experiences and the experiences in our bodies. She directs her thinking in a way that she has a lot of reflexivity in her scholarship and her experiences. By exploring her own experiences, she also expands on the meaning of the ‘liminal’.

“I was able to recount an experience that is also the subject of my book project and it’s an experience that evokes a lot of these stereotypes and the material and symbolic violence. These are stereotypes that are attached to a person of my identity and a person of my citizenship. In my introduction to the post [above], when the taxi driver thought I was a nanny, I think this is one of the moments that I recognised as disorienting. It’s a terminology that I’ve learned from Ian Williams, a Canadian scholar who talks about those small microaggressions that are constantly being thrown at you as a person of colour [POC] in North America. It doesn’t really hit you immediately as something offensive or meant to be offensive, but it also takes a while for you to realize that it’s a microaggression.” – Rina

She goes on to discuss how microaggressions like this are often thrown at POC in North America and other parts of the Global North. Often, people don’t realise immediately that the words directed at them were offensive, it sometimes takes a while to realise that these are microaggressions.

“I want to lead with that story because this is the reality of so many documented and undocumented migrant Filipinos, especially Filipina workers all over the world. The project of globalization and the project of wanting to secure national growth for the Philippines in the 70s. And the Marcos dictatorship was to ensure that migrants leave the Philippines and go to different countries so that they remit money back to the Philippines. And this project has been continuing until now. So many of my friends have opted to leave the country. I am one of them.” – Rina

One of the readers asked about the notion of flying as both privilege and peril and for her to expand on this.

“My mother was a breadwinner. It’s now becoming a very common thing that Filipino women are seen as breadwinners of basically the Philippine society, a lot of us move, a lot of us fly, a lot of us do a lot of things just to keep the family going. But my dad always used to remind me to be prepared for anything that might happen. He says that every time my mother flies or goes on a flight, half of her body is buried six feet underground. That might seem quite awful to hear, but that’s the reality that I grew up with. I had an understanding that every time you fly, there’s always peril that goes with it and it’s not, you know, not just getting from one destination to another, I think. Part of my work in migratory consciousness is also me trying to understand what happens in the in-between because my mother’s identity was always collapsed or engulfed in the capacity to care, nurture and provide financially for the family. And she provided financially extraordinarily well. However, I think what was missing for me was: Who was she? When she was in another country, who was she? Without the family, without that image of a breadwinner.”

“I don’t think that it’s just from one end to another. There’s always the in-between that I’m conscious of and that’s part of migratory consciousness. I feel that. We’re just so constantly busy trying to prove ourselves to be one thing after another, trying to be something trying to be this identity that our country asks of us, and then this new space foreign land asks of us.” – Rina

Rina goes on to discuss how there is an ‘inbetweeness’ where one is lost in the liminal environment, losing agency to choose. A reader asked about her definition of home.

“In my field, at least, move away from the emphasis on place and the kinds of arguments that compound that concept. We should think about home as not just one place anymore – connections and multiple lines on the map that creates an individual.” – Rina

Rina discusses this notion of home within the literary community, between oceans and lands.

“I am trying to find my way in the literary and academic community here in Canada and in North America in general, while still trying to keep the ties with my fellow academics back in the Philippines. It’s a dance.”

“I think like in my perspective and in my experience, I get to think of it because I’m in the space to think of it I’m very lucky to think in that space and that’s why my poems as well, aside from autoethnography, in my scholarly work, and my poems are quite personal as well because I constantly am trying to find connections. I’m always constantly trying to reach out.” – Rina

A reader asked about her view on the oceans being a metaphor for languages as fluid and in-between.

“So many people choose to speak the dominant language of whatever country they have migrated to and that it’s not just the loss of culture and language of origin necessarily, but also it reproduces the dominance of North Europe. Whether it’s Germany, the USA, etcetera, because the languages we choose to speak and become our dominant language will become our first language, as opposed to our language of origin ends up being usually a European language, which is oftentimes English, actually. And then following from that, usually German.” – Reader

Another reader went on to call on their own experiences of home languages and identity in their migration.

“I’ve just been reading Robin Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass…she had this beautiful chapter where she talks about how, as an Indigenous American, she doesn’t speak her language, right? She just has words for things, and that’s how I feel. You know, I just have words for nouns and things, but I can’t complete proper sentences. And is that a loss that should be mourned, or do we accept that we evolve into, you know, the deed asked about the migrant consciousness? What is the migrant consciousness? Is it this kind of a loss of cultural origins, of language? Some people choose food as an expression to protect themselves against that loss. Should we be mourning, or should we, in fact, embrace it as evolving into a new person, and that person is not necessarily a lucky person, but just a different person?” – Reader

Rina responded through her personal experiences of Tagalog and English.

“Should it be mourned? I think this is because a lot of my concept of a migratory consciousness really stems from my wanting to have agency over my experiences. A lot of our choices are taken out of our hands, right? I find that, for example, I have to, for example, give money back to my parents for a long time. That was a choice initially made and then eventually it was taken out of my hands as the needs became greater and greater and more family members needed more things and as a student that was really hard to juggle – and that’s expected. It is all part of the remittance economy.”

“Tagalog was considered the kind of language of the working class, and it’s such a sad concept and development and you know, let’s be honest, it’s the continuation of colonial violence. Colonisation is still very much, you know, alive and thriving. Even within these countries where they’re no longer unoccupied by the coloniser” – Rina

This reflection linked to the previous talk by Nazry Bahrawi, where we briefly discussed language and colonisation (thinking back to Ngugi wa Thiong’o), the dominance of European languages in the academy, and in daily life. Colonisation resulted in cultural genocide, and this coloniality in the use of dominant, European languages, is a continuation of this colonial project.

“I’m thinking of how important oceans and water are to you and thinking about, for example, your poems covering submerged reefs. You know, not only is it kind of subversive in itself, but it is submerged in these kinds of watery fluid narratives, and I think it’s really interesting when we think about this idea of migration and home and water as a substance that’s kind of challenges the concept of borders. It fights against that because you can’t. You can’t really contain water. You can’t put a wall across the ocean and be like ‘this is this is my ocean’. That’s just not gonna work. So, I’m interested to think about that in terms of non-human life and how migration is such an integral part of oceanic life. Also, it’s something that’s been happening for thousands if not millions of years.” – Reader

“These perspectives of centralising climate change at the expense of understanding other, perhaps more crucial factors, and the fact that for a lot of these people from lower or socioeconomic backgrounds or from marginalised parts of the world, Global South countries and so on. Climate change is not the first crisis- just something that came on top and it can be reductive to just see them as climate migrations when they’re more complex than that.” – Reader

“Eco-criticism is a framework or analytic that helps to explore these factors. And it’s not just climate change, it’s not just, you know, dispossession. It’s all these other things, and we can look at these and give them equal space and critique.” – Rina

“I think it’s really important that this work isn’t just carried by you know, minority communities, but also by white critics, white people, generally white communities, you know. This is something that needs to happen collaboratively. It should not be the responsibility solely of people…to kind of challenge these narratives and to fight against and work against colonisation, or Western narratives. One of the things that you’re really showing in your poetry is this kind of visual element and you really challenge sort of Western expectations of form through this visual merging. I was kind of curious whether that was something that you actively did in the sense of wanting to challenge Western expectations of form, or whether this was something that felt quite natural to you or kind of just speaking about that kind of aspect of your work.” – Reader

“I was schooled in poetry. I think a lot of us who grew up in postcolonial environments or schooled in traditional British Euro-American forms of writing, that was how I came upon poetry, but I think when I came to this creative practice, it’s really finding where I’m most comfortable. And again, it’s in the liminal environment, in the liminal space, in-between” – Rina

*These minutes have been edited and selected by the author and editor, based on the arc of the conversation and the multiple perspectives offered.

Final thoughts

The session began with a reading of the poem, “Corridor Stories II,” from my forthcoming poetry collection, A Geography of (Un)Natural Hazards. This poem is a response to the violent killing of a Filipinx receptionist and single mother in her workplace, in Toronto, Canada by a disgruntled white teenage boy. It was followed by the percolation of ideas, narratives and conversations amongst the small group of engaged readers who were equally invested in the intersections of migration, neocolonialism, ecological disasters and globalisation. This reading group allowed us to pause and think about individual life experiences of living in spaces rather than places. Such a pause included moments to discuss our agencies in the movements we have undertaken – whether by choice or force.

After the session, I think about what a turn towards decolonial thinking means for many of us who are deciding on where to live, where to move, where to thrive and where to survive. So many of these decisions have been stolen from us by the interlocking systems of oppression that have actualised world systems into the realities we live in at this temporal moment.

I was reminded in the session that many of us are opening up to the possibilities of constantly being unsettled – in terms of our identities, professions, scholarships, writings and life choices. What does it mean, especially for those who identify as women, to be constantly unsettled in the face of environmental collapse? What do we do to gain what we have lost? These answers will not come easily, perhaps not in our lifetimes, but will be incrementally revealed as we take each uncomfortable step into the possibilities and promise of a decolonial space.

Citation

Chua, R.G. (2023) “a steering to homes, or toward a migratory consciousness in ecocriticism.” Journal of Southeast Asian Ecocriticism, 1(2): 111-122.

Xiaojing, Z. (2021) “Introduction: Migrant Ecologies as a Site of Critical Inquiry” in Migrant Ecologies, ed. Zhou Xiaojing and Zheng Xiaoqiong, Lexington Books/Fortress Academic: 1-19.