What does anthropology, burdened by its own colonial history and currently undergoing its own decolonisation, have to offer to decolonial scholarship?

It is irrefutable that anthropology, for much of its history, was a tool of the colonisers. Standing Rock Sioux activist and scholar, Vine Deloria Jr., confronted anthropologists with a bitter anecdote: ‘Indians are certain that all societies of the Near East had anthropologists at one time because all those societies are now defunct’. The second half of the twentieth century has witnessed the coming of a new generation that puts so much interest in self-correction and, by continuing the work of early 20th century anti-racism scholars like W. E. B. Du Bois and Antenor Firmin, speaks to the interests of people at the periphery of power. Current anthropologists engage their work with feminists, critical race theorists, and native studies scholars, and also collaborate in a meaningful way with local communities. Decolonisation in anthropology manifests in various ways that aim to elevate the position of the vernacular communities that anthropologists work with within the hierarchy of epistemological and structural power.

My scholarship is shaped by four major areas: Anthropology, global health, and science, technology and society (STS). In this reflection, I want to point to two features in anthropology that can be contributive to decolonial scholarship. Next, I also want to put this contribution in context relevant to my research.

Ethnography (or writing about culture), as a data collection method or as a product, is a powerful methodological tool that anthropology proudly brands as its unique asset. However, it is anthropology’s newfound methodological interest in relativism that might mark its biggest contribution to decolonial scholarship. At the centre of this intervention, it is Franz Boas’s cultural relativism that was then championed by the decolonial generation of anthropologists. With cultural relativism as its powerful lens, anthropology today can position the communities it studies as experts in their own right, thereby moving away from theories that continue to position Euro-American scholars as the expert.

Today’s colonialism is the by-product of converging globalised capitalism and entrenched neocolonial structures. Colonisers nowadays come with a different rule of play, with a skin color similar to the skin color of the people they colonise, a similar robe that masks their true intentions. While today’s colonialism differs in many ways from its old form, it still has its very nature: The universalisation of a particular idea that is rooted in one cultural tradition. Universalisation is more about the idea of power than the power of an idea.

My research applies cultural relativism as a decolonial lens to technological universalism. My target is vaccination. Vaccination, like many other modern technologies, spreads widely not because the idea is universally unchallenged, but because power becomes the pushing machine. In the past, vaccination spread out through colonial vessels and the arms of slaves. Now, vaccination spreads because of what Da Costa and Da Costa have called ‘multiple colonialisms’: A powerful hierarchy of global-national actors that makes possible a system to rule from afar. Within this hierarchy, postcolonial country administrators are ironically positioned as the long arm of colonialism.

The core argument of cultural relativist-inspired decolonial critique is that all knowledge systems are symmetrical and equally valid. Therefore, all cultures have to be studied within their own historical contexts. In my presentation, I reflect on the idea of tidak cocok (incompatible), a local term used by my Muslim interlocutors in Banda Aceh to explain their reason behind refusing measles-rubella vaccines contaminated with pork materials. Deeply driven by local interpretations of Islamic values and collective trauma, tidak cocok fosters a sense of liberation, paving a pathway to refuse universalised yet unfit tools and systems. Tidak cocok reclaims what has been marginalised, delegitimised, and ignored by dominant epistemic and political structures.

As Abimbola and Pai assert, global health is not intended to survive its decolonisation. Even nowadays, global health still suffers from its white-savior mentality as a consequence of its direct transformation from colonial medicine. Moving away from its universalist epistemology to begin embracing the relativist idea of human health is one urgent step in decolonising global health. But, as many current anthropologists also reflect on their own research practices, only embracing cultural relativism will not be enough for decolonisation.

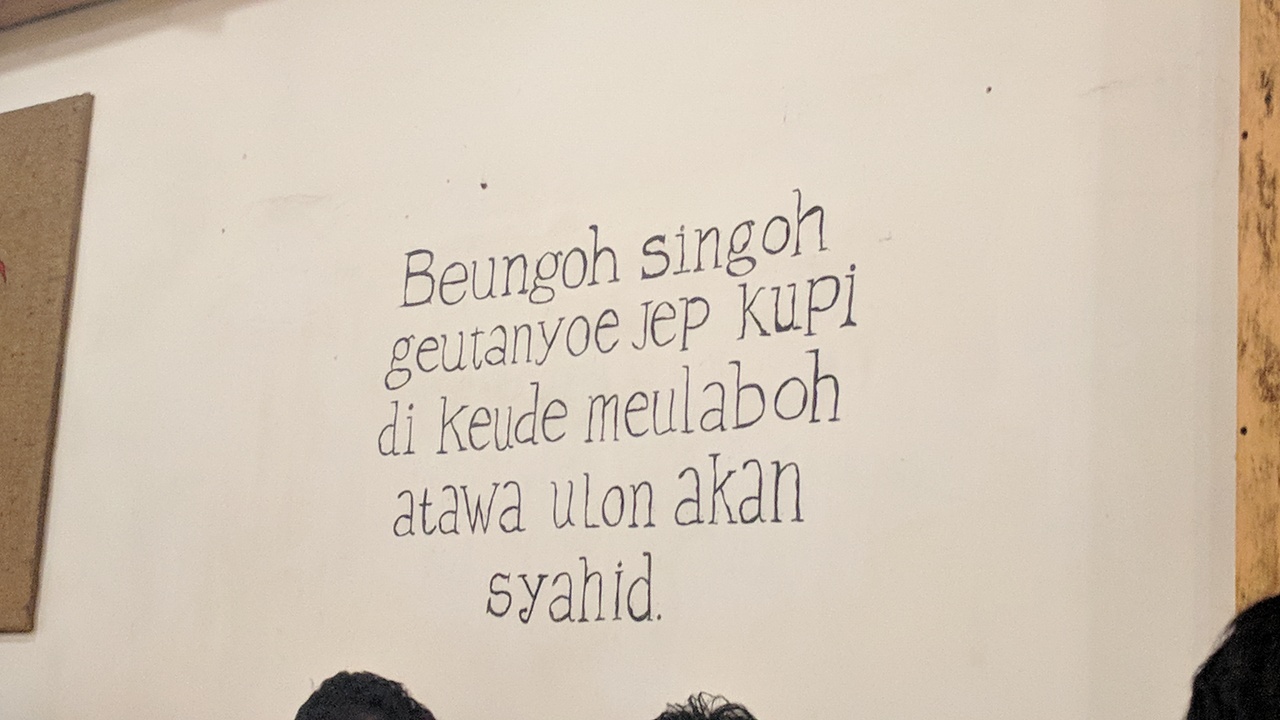

Photo by the author: Famous words from an Acehnese anti-colonial fighter, Teuku Umar (1854-1899), printed on the wall of a coffee shop in Banda Aceh.

Reading group event details

Date: 29th October 2025

Title: Incompatibility, decoloniality, and vaccine hesitancy with Dimas Iqbal Romadhon

Speaker: Dimas Iqbal Romadhon

Chair: Nazry Bahrawi

Minutes by: Claire French

Selected minutes

Nazry (Chair):

Hello everyone, thank you for coming. I think we can begin the discussion. We’re planning to run this for about an hour. We’ll start with Dimas’ presentation and then move to questions after that.

I’m Nazry. I’m an assistant professor at the University of Washington in the Southeast Asia program, and I worked with Dimas when he was a PhD student here. He is now a research fellow at UC Davis working in medical anthropology.

Dimas (Speaker):

I remember talking with Nazry about the possibility of presenting my research – specifically one of my dissertation chapters – for this ‘Reading Decoloniality’ study group. At that time, the paper was still a very rough draft. I was hoping to use this session as a workshop on how to develop the paper and engage more deeply with ideas of decoloniality before publication.

However, as time went by, the peer-review and editorial process moved very quickly, and the paper was published just last week. So the idea of a ‘workshop’ in the strict sense is maybe less relevant now, but I still hope to get your comments to shape my future research trajectories.

I’ll begin with some larger ideas about how this project started and how I approach the issue, and only then move more specifically to what I wrote in the article.

Because I know there are several scholars here from formerly colonised countries who are also non-native speakers of English, I want to begin with a story. After I received the proofs for the article, I tried, just for fun, the language-editing ‘verdict’ service offered by the publisher, which normally costs around 300–500 USD. I uploaded my proof and received a score of 37%, with a warning that there was a high chance of rejection because of the language.

I was shocked. It really highlighted for me how colonialism, language, and automated language-checking are intertwined in a way that makes ‘good English’ more important than the ideas themselves. I am grateful that the journal which published my article does not submit to that practice, because otherwise it might have been rejected.

I want to begin the substantive part of the presentation with a map of the spread of vaccination in the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea. We all know the popular narrative: Edward Jenner discovers vaccination, and from there we get this triumphant story of the ‘glorious era’ of vaccines. What is often missing from that narrative is a map of how vaccines – the idea, the material technology, and the people who carried them – travelled through colonial institutions.

In the case of Java, the practice of vaccination arrived through the arm of an enslaved person sent by the French, under a French lieutenant general, as part of Napoleonic manoeuvres in the region. At that time, Jenner himself reportedly felt frustrated with the British Empire and admired the French Empire’s ability to push vaccination into many parts of the world.

I show this map to make the point that vaccination has been deeply colonial from the very beginning. I am not talking about variolation here, but about vaccination – the more scientifically modified or ‘improved’ version.

When I started this research, I drew inspiration from Juno Salazar Parreñas, who argues that orangutan rehabilitation is an institution shaped by colonialism. By analogy, I see vaccination as a similar institution, rooted in colonial histories. As many scholars, including Professor Celia Lowe who is currently here among us, have pointed out, vaccination continues to carry many of the same features it had in the colonial past; it has not changed as much as we might imagine.

My research asks: How do these colonial features appear in contemporary vaccination practices in Indonesia, and what do responses to these colonial features look like?

This project is part of a larger research agenda that I hope will eventually become a book and several articles. The broader timeline begins with the 1998 political reform (Reformasi) in Indonesia, which created space for democratisation and, importantly, for Islamic voices to become more dominant in public discourse.

I focus in particular on how Islamic discourse has helped create a pathway for the ‘decolonisation’ of vaccination in Indonesia by raising concerns about the use of pork-derived materials in vaccines.

Part of my research looks at debates among different Islamic schools of thought on pork contamination and at how various political actors contribute to a messy, multidirectional and sometimes deceitful process that is described as ‘scientific independence.’

For today’s presentation, I focus on what happened in 2018, when concerns about pork contamination in the measles–rubella (MR) vaccine led to the failure of a 100-million-dollar vaccination project in Indonesia.

In 2018, Indonesia launched a very ambitious mass vaccination campaign targeting 67 million children. The budget was around 100 million USD, making it perhaps one of the largest campaigns of its kind. Because of Indonesia’s size and archipelagic geography, the logistics were already complex.

During the launch, there was a somewhat revealing moment. The President, Joko Widodo, invited a middle school student who had just been vaccinated to the stage and asked him whether he knew what vaccine he had received. The student had no idea. This surprised many people: here was a massive, nationally significant campaign, yet the direct subjects of the campaign were not told – or did not understand – what was happening to them.

Soon after the launch, concerns began to circulate that the MR vaccine had been contaminated with pork-derived materials and human diploid cells. A majority of Indonesian parents are Muslim, and they began to voice concern that the vaccine might be haram. They requested that the Indonesian Council of Ulama (MUI) conduct a halal examination.

MUI ultimately confirmed that the vaccine did indeed involve pork-derived substances and human diploid cells. The government responded by suspending the vaccination program, on the grounds that it was incompatible with the religious identity of the people. Some commentators then observed that the fatwa on the MR vaccine drove immunisation rates down dramatically; by the end of the campaign, coverage was as low as 7% in some areas.

After the rumours about pork contamination spread, the local government in Aceh suspended the vaccination program. Other provinces, such as Riau and West Nusa Tenggara, also expressed discontent and refusal, but the key difference in Aceh was that the local government actively sponsored the refusal. That is an important point of interest in my analysis: why is the vaccination refusal in Aceh so strongly supported by the provincial government?

My ethnographic work in Aceh began with this question.

The photograph I show in the slide is of the Kodam Iskandar Muda military base, the Indonesian army’s territorial command for the Aceh region. Behind the base there is a coffee shop where I met a man named Abdullah. He told me he was a lecturer at a private university. I still have questions about why he was there that morning and why he seemed to know many military officers, but those remain open.

Abdullah is a father of two. When I asked whether his children had been vaccinated, he said no, none of them had ever received vaccines. When I asked why, he answered simply: the vaccine was tidak cocok for Acehnese.

This term tidak cocok is very familiar in Indonesia. It means that two things cannot and should not go together. For example, when couples divorce, they often cite tidak cocok as a shorthand justification. The reasons might be complex, but tidak cocok is an accepted way of naming a fundamental mismatch. It can also be used to explain why a particular medicine works for some people but not for others: obatnya tidak cocok – the medicine is not compatible with that person’s body.

Those familiar with Indonesian literature might recall a famous poem by the Indonesian poet Rendra that uses tidak cocok to criticise centralised state policies that do not fit the needs of ordinary people and instead serve elite interests.

As a lens for power and decolonisation, tidak cocok – especially when uttered by vernacular speakers – can function as a political statement: some things cannot be reconciled, not simply because they are ‘different,’ but because there is a fundamental misalignment in history, power, and future imaginaries.

In Aceh, vaccine hesitancy exists along a spectrum – as it does elsewhere – ranging from delay and cancellation to questions and doubts. But at first glance, what I found was silence: people simply did not want to talk about vaccination. When medical officials tried to discuss it, people would quickly change the subject.

So this seemingly mundane phrase, tidak cocok, became my entry point into thinking about coloniality. It allowed me to ask how everyday language encodes political critique.

There are two major narratives deployed by outside observers about the vaccination refusal in Aceh. First, it is an expression of religious fundamentalism, and second, it is a specific response to the confirmed contamination of the MR vaccine.

I argue that both explanations miss something crucial. Even before 2018, vaccine confidence in Aceh was already very low – among the lowest in the country. During COVID-19, a good Al Jazeera article came to a similar conclusion: that old wounds from past conflict and military violence continue to fuel vaccine hesitancy in Aceh. In other words, patterns of refusal are connected to collective trauma generated by decades of human rights violations by the Indonesian military. There is an everyday suspicion of anything that comes from the central government.

Discourses of ‘Indonesian colonialism’ in Aceh often circulate at the grassroots. For example, just months before I arrived in 2019, one local elite – who later became governor – announced that he wanted Aceh to have a referendum and possibly separate from Indonesia. Many people I spoke to did not reject that idea outright. Their questions were more pragmatic: could Aceh sustain itself after separation? This is a fundamental question considering Aceh infrastructure is very dependent to the Indonesian government and its neighboring regions. For example, basic needs such as electricity are still supplied from the neighbouring province of North Sumatra.

So the central question for many is not simply, ‘Do we want independence?’ but ‘Can we survive materially after independence?’ This dynamic forms one layer of the social context in which narratives of vaccine hesitancy circulate.

On another level, there is a political and structural disconnection between global health agencies and the Indonesian state.

Indonesia has had its own measles-only vaccination program since 1982, supplied by domestically produced vaccines from a company called Bio Farma. Around 2012, the global Measles & Rubella Initiative recommended shifting from measles-only to measles–rubella (MR) combination vaccines for global campaigns. Member countries were expected to adjust their domestic programs accordingly.

The recommendation offered several options: MR, MMR (measles–mumps–rubella), or MMRV (measles–mumps–rubella–varicella). In Indonesia, the recommendation was translated into the use of MR vaccines, largely because they were more economical than MMR or MMRV.

However, many physicians and paediatricians in Indonesia – including doctors I interviewed in Aceh – complained that focusing only on measles and rubella excluded mumps and varicella, which are also prevalent.

Technologically, the shift from measles-only vaccines to imported MR vaccines meant that domestically produced vaccines, which had been certified halal and adapted to local climatic conditions, were displaced by foreign-made vaccines. The new products required cold-chain infrastructure that is challenging to maintain in Indonesia’s hot climate. Culturally, they introduced an additional burden in the form of religious concerns about pork-derived materials.

This multilayered dynamic reflects what Dia da Costa and Alexandre da Costa call multiple colonialism: we live in a colonial present marked by coexisting, overlapping forms of colonial power. Initially, I thought the main relationship I was studying was between Indonesia and Aceh, but I realised that Indonesia itself is also a ‘long arm’ of global vaccination regimes. Indonesia occupies a strange position: colonised at one level, while practising internal colonisation at another.

In the paper, I use the narrative of incompatibility to understand how coloniality plays out in this landscape of multiple colonialisms.

In my article I work with three kinds of incompatibility.

First, there is Abdullah’s joke: that Aceh has the largest pig population because pigs flee from Medan, where people eat them, to Aceh, where everyone is Muslim and no one eats pigs. The pigs ‘live happily’ in Aceh. The joke encodes a sense that pigs and Acehnese Muslims are fundamentally incompatible, but in a way that is humorous and politically resonant.

Second, there was a conversation with a local coffee shop owner about science and about interspecies DNA research. From a scientific standpoint, his understanding may not be ‘correct,’ but what matters for me is not scientific correctness. What matters is the political agency of his statement: once a vaccine has been contaminated with pork, it becomes incompatible with a Muslim body and cannot be accepted.

This reminds me of Frantz Fanon’s formulation of the colonial dilemma: ‘become white or disappear.’ In this case, the Muslim identity and its ethical preferences are not respected by the vaccination regime. The implicit message is: accept the vaccine as it is, or be excluded, unheard, and perhaps the worst, demonized.

Third, I look at how the official mechanism for addressing alleged vaccine allergies also becomes incompatible from the perspective of patients. In theory, there is a system that could acknowledge adverse events, but in practice it does not represent patients’ interests. A small group of experts defines what counts as an ‘allergic reaction.’ In one case, a primary school student was paralysed after vaccination. His parents tried to hold the government accountable, but the expert committee concluded that what happened did not qualify as a vaccine allergy. The definition is tightly controlled, and that control itself becomes another form of incompatibility.

After more than a month of suspension, the Aceh government began to reconsider the MR vaccination. In meetings, many narratives circulated. Senior officials expressed concern that the principle behind the program was not compatible with Acehnese circumstances and that the situation in Aceh was not as ‘emergency’ as in Jakarta.

Vaccine hesitancy scholarship from other parts of the world has found similar patterns: the key issue is often not whether the vaccine ‘works,’ but why vaccination is prioritised above other urgent problems, and who has the authority to decide that hierarchy of urgency.

Finally, the local Ulama Council chair allowed vaccination to resume, but on the basis of a religious principle of emergency, which is different from the public health notion of emergency. The requirement to wait for a religious ruling turned vaccination from a public health issue into a religious one, creating a further crisis of public health authority.

From following these narratives in Aceh, I propose that incompatibility – tidak cocok – can be understood as a lexical item of coloniality. It can foster a sense of liberation by enabling refusal. By engaging with anthropological scholarship on refusal, we can see tidak cocok as a pathway to reject tools and systems perceived as unfit for situated knowledges and historical experiences.

At the same time, it allows people to reclaim what has been marginalised or delegitimised by dominant epistemic and political structures. When they say something is tidak cocok, they are asserting their right to expertise and to identity.

Regarding the prominence of Islamic expressions in the context of vaccine hesitancy: my view is that Islamic discourse does not in itself generate hesitancy. Rather, a decolonial perspective motivates much of the refusal, and Islam provides a distinct local idiom or flavour through which that critique is articulated. This is something I continue to work on in the broader project.

Thank you, and apologies for taking so long, partly due to technical glitches.

Reader 1:

I have been working through these ideas and I understand tidak cocok as a form of epistemic incompatibility. One could also call it cultural incompatibility, but that risks trivialising it, because ‘culture’ is often reduced to mere practices.

So I read this as an epistemic incompatibility, and you’ve talked about the liberatory dimension of calling out this incompatibility. I am curious: through that act of calling out, what exactly is liberatory?

You talk about interlocutors and about knowledge becoming shared. Through calling out incompatibility, the knowledge becomes legitimised and perhaps forms a new centre – in a ‘multiple centres’ sense.

So when you describe this as liberatory, do you mean that:

– it feeds back into institutions in order to change them, or

– it creates multiple centres that might rival existing institutions in representing the epistemologies of the people you discuss?

That is my question.

Dimas:

Thank you for the question.

Because of my training in anthropology and because my writing engages directly with public health issues, my language often leans towards applied anthropology. In that spirit, I think de-centring is very relevant here.

By voicing that there is a local identity that vaccination cannot simply ignore, people are effectively demanding that vaccination practices be modified. Right now, the model is that ideas about vaccines are developed in one place, the vaccines are manufactured in another, and then circulated globally. In this case, the MR vaccine used in Indonesia was produced in India, which itself has a complex position in the history of coloniality.

The demand emerging from Aceh and other contexts is for modification and adjustment at the level of the country or region itself, rather than simply waiting for global institutions to decide what is suitable. In an ideal – perhaps utopian – future, every country could develop vaccines suited to its own epidemiological, climatic, and ethical context, and be ready to contain outbreaks originating anywhere. Indonesia does have the capacity to create its own vaccines, but this capacity is constrained by global corporate structures and the political economy of global health. We need to be critical about how these global corporations operate and what kinds of relationships they create and sustain.

Reader 2:

You quote Alpha Shah, who warns that decolonial rhetoric can be hijacked. I appreciated your reading of vaccination refusal as a colonial refusal.

But at what point do we become cautious about reading such refusals positively, especially when they intersect with religious or far-right ideologies? I’m thinking, for instance, of Arab countries with authoritarian regimes.

How might vaccine hesitancy exist along those lines in other contexts?

Dimas:

The rise of Islamist political power in Indonesia is indeed important for this discussion. I want to be careful when talking about religious identities and beliefs. We need to recognise that particular strands of Islam can be, and sometimes are, hijacked, and we have to be alert to that.

The Aceh case is the first context that I have analysed in depth. In other chapters of my project, I look at the agency of Indonesian Muslims in different class positions. For example, some middle-class Muslims refuse vaccines provided by the Indonesian government and travel to other countries to receive vaccinations that they perceive as more compatible with their ethical concerns.

I hope to capture the diversity of agencies and narratives circulating in Indonesia in response to pork-contaminated vaccines – and more broadly, to the messy process of vaccination in a postcolonial context.

Nazry:

Your presentation reminds me of Walter Mignolo’s work. At one point, he spoke positively about Singapore’s authoritarian leader, which raises questions about how decolonial theory engages with authoritarianism.

I am also thinking about what is universal and what is contextual. How do we do decolonial scholarship that aspires to theorise in a universal way, while still attending to specificity? Is anthropology still relevant to that task?

Dimas:

I would say that I challenge the universality of much theory.

Anthropology, at this moment, has an opportunity to align itself more closely with the communities it studies, rather than treating them merely as sites for extracting data to feed into global theoretical projects. Anthropology can work against universalist tendencies by grounding theory in particular contexts and histories.

Reader 3:

Anthropology, as you suggest, can challenge the universalist theorising that sometimes occurs in decolonial studies. Decolonial work can, at times, miss the specificity of certain contexts.

This is what I find so interesting in your argument: when people say ‘it’s incompatible for us,’ they are not just making a surface-level claim. The incompatibility reaches deep into entire epistemologies that have diverged from dominant ones at some point in history.

Nazry:

When I think about Southeast Asian Studies, I remember that it emerged as an area-studies project in a Cold War context, with the United States trying to understand the rest of the world.

Now, new scholarship from within Southeast Asian Studies is emphasising particularities and challenging those older, strategic frameworks. Your work speaks to that shift by insisting on the importance of local histories and epistemologies.

Dimas:

Decolonial studies is actually the last scholarly community I would have thought would be engaged in this project, so I’m especially happy to receive your comments. They help me think through how to position this work in relation to both anthropology and decolonial theory.

Reader 4:

There has been an erasure of many Black communities’ refusals of vaccines in global discussions. Thank you so much for bringing in these Indonesian and Acehnese examples. It is important to share them, as they help us see vaccine refusal and decolonial politics in a more complex and global way.